There’s an ancient Chinese curse or proverb: “May you live in interesting times…”

There’s an ancient Chinese curse or proverb: “May you live in interesting times…”

Well, there isn’t actually (it dates all the way back to the politician Austen Chamberlain in 1936) but I think we can all agree that 2016 has been… interesting!

Most of us would probably wish that 2017 is a little less so.

While Westminster Libraries can’t promise world peace or political stability, we can promise you some interesting anniversaries and the resources for interested people to carry out further research.

January

The year kicks off in January with the 75th anniversary of Desert Island Discs, which was first broadcast on 29 January 1942. It continues to this day with guests (rather tweely known as ‘castaways’) being asked to discuss the eight pieces of music they would take to a desert island. Later on, guests were allowed to choose a book and a luxury too. The first castaway was the ‘comedian, lightning club manipulator, violinist and comedy trick cyclist’, Vic Oliver. Oliver was not only a major star on the radio but also the son-in-law of Winston Churchill (something Churchill wasn’t too thrilled about, though Oliver never traded on the relationship). Though this episode doesn’t survive in the BBC archives, many hundreds of others do and are available to listen online or download as podcasts. The earliest surviving episode has the actress Margaret Lockwood as a guest and other castaways include seven prime ministers, dozens of Oscar winners, a bunch of Olympic medallists, a few Royals and several criminals.

February

19 February brings the 300th anniversary of the birth of the actor, playwright and theatre manager David Garrick. Though he was a native of Lichfield (and former pupil of another Lichfield resident-turned-London-devotee, Samuel Johnson) by the age of 23, Garrick was acclaimed as the greatest actor on the English stage. He was a noted playwright but most famous for his Shakespearean roles – though he was not averse to ‘improving’ on the text – his adaptations included a Hamlet without the funeral of Ophelia and the need for the gravediggers, a ‘King Lear’ without the Fool and a Cordelia who lives on, an interpolated dying speech for Macbeth and a scene between the two lovers in the tomb before they die in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Be honest – who wouldn’t want to see those? He ran the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane for nearly 30 years and he is now commemorated by a theatre and a pub (with Charing Cross Library neatly sandwiched in between).

March

1717 wasn’t just a significant year in the history of ‘legitimate’ theatre. 2 March that year saw the first performance (at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane) of The Loves of Mars and Venus by John Weaver, generally regarded as the first ballet performed in Britain. While there had been English masques and French ballets before this, Weaver was the first person to tell a story through the medium of dance without the need for songs or dialogue. Weaver was the son of the dancing master at Shrewsbury School (public school curricula must have been rather different in the 1600s).

_dressed_as_a_harlequin,_attributed_to_John_Ellys.jpg) In 1703 he had staged (at Drury Lane) a performance called The Tavern Bilkers, usually regarded as the first English pantomime (he described it as “the first entertainment that appeared on the English Stage, where the Representation and Story was carried on by Dancing Action and Motion only”) but it was The Loves of Mars and Venus (the choreography of which survives) which established Weaver as the major figure in English dance until the twentieth century. Venus was played by Hester Santlow (shown dressed as a harlequin), one of the leading ballerinas of the day, who created many roles for Weaver.

In 1703 he had staged (at Drury Lane) a performance called The Tavern Bilkers, usually regarded as the first English pantomime (he described it as “the first entertainment that appeared on the English Stage, where the Representation and Story was carried on by Dancing Action and Motion only”) but it was The Loves of Mars and Venus (the choreography of which survives) which established Weaver as the major figure in English dance until the twentieth century. Venus was played by Hester Santlow (shown dressed as a harlequin), one of the leading ballerinas of the day, who created many roles for Weaver.

April

Readers of a certain age will remember adverts for Memorex tapes (other brands are available) in which a singer shattered a glass with a high note and the trick was repeated when the tape was played back. Depending on exactly how certain your age is, you may have identified the singer as the great Ella Fitzgerald whose centenary is commemorated on 25 April 2017.

Growing up in a poor district of New York and orphaned in her early teens, Ella spent time in a reformatory but soon escaped and began to enter show business via talent competitions and amateur nights, becoming an established band singer. At the age of 21 she recorded a version of the children’s nursery rhyme A Tisket A Tasket which went on to sell over a million copies. She went on to become one of the greatest of all jazz singers, developing her own idiosyncratic style of ‘scat singing’. All through her career she fought prejudice, refusing to accept any discrimination in hotels and concert venues even when such treatment was standard in the Southern USA.

You can listen to some of her greatest recordings via the Naxos Music Library and learn more about her career in Oxford Music Online (log in to each with your Westminster library card number).

May

May Day has long been a festival associated with dancing and celebration and more recently with political demonstrations. But 1 May 1517 has become known as Evil May Day. Tensions between native Londoners and foreigners lead one John Lincoln to persuade Dr Bell, the vicar of St Mary’s, Spitalfields to preach against incomers and to call upon “Englishmen to cherish and defend themselves, and to hurt and grieve aliens for the common weal.”. Even though the Under-Sherriff of London (none other than Sir Thomas More) patrolled the streets, a riot broke out when they tried to arrest an apprentice for breaking the curfew. Soon afterwards, a crowd of young men began to attack foreigners and burn their houses. The rioting continued throughout May Day – fortunately, while some houses were burned down there were no fatalities. More than a thousand soldiers were needed to put down the riot. Lincoln and the other leaders were executed, but most were spared at the instigation of Cardinal Wolsey, who according to Edward Hall

‘fell on his knees and begged the king to show compassion while the prisoners themselves called out “Mercy, Mercy!” Eventually the king relented and granted them pardon. At which point they cast off their halters and “jumped for joy”.’

Sadly this was not the last outburst of anti-foreign feeling in London’s history but such incidents are thankfully rare.

June

A happier event took place on 30 June 1997 with the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by JK Rowling. It’s hard to remember a time when we didn’t all wish we’d received our letter to Hogwarts instead of going to a boring Muggle school.

A happier event took place on 30 June 1997 with the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by JK Rowling. It’s hard to remember a time when we didn’t all wish we’d received our letter to Hogwarts instead of going to a boring Muggle school.

But we all know about Harry so let’s move on.

July

To 12 July and first documented ride, in 1817, of the ‘dandy horse’ or ‘running machine’ or, to you and me, a bicycle without chains or pedals. This was the first means of transport to make use of the two-wheel principle and the creator was Baron Karl Drais , perhaps the most successful inventor you’ve never heard of, and he managed an impressive 10 miles in an hour. While it looks pretty clunky by today’s standards, Drais was inspired by the Year without a Summer of 1816 when crops failed and there weren’t enough oats to feed horses.

Readers of Georgette Heyer’s Regency romances may remember thar Jessamy in Frederica was very proud of his skill with the ‘pedestrian curricle’. The Observer newspaper was enthralled by the invention of ‘the velocipede or swift walker’ claiming in 1819 that, on a descent, ‘it equalled a horse at full-speed’ and suggesting that

‘on the pavements of the Metropolis it might be impelled with great velocity, but this is forbidden. One conviction, under Mr Taylor’s Paving Act, took place on Tuesday. The individual was fined 2/-.’

When he wasn’t inventing bicycles Karl Drais was making an early typewriter, a haybox cooker and a meat grinder.

And on 27 July 1967, we note the 50th anniversary of the decriminalistion of homosexuality. This will be celebrated with many events throughout the year such as this one at Benjamin Britten’s home and others at various National Trust properties.

August

Most of us can probably remember what we were doing on 31 August 1997 when we heard of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales and she will be on many people’s minds as the 20th anniversary of this event approaches.

A slightly more auspicious event took place on 17 August 1917, when the two war poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon met at the Craiglockhart War Hospital, an event written about by Pat Barker in her novel Regeneration, as well as Stephen Macdonald’s play Not about Heroes. Owen wrote two of his most beloved poems – Dulce Et Decorum Est and Anthem for Doomed Youth while he was in hospital (he also edited The Hydra, the patients’ magazine) and was tragically killed the following year at the very end of the war. Sassoon survived the war and wrote about his hospital experiences in the autobiographical novel Sherston’s Progress. You can read more about the lives of Owen, Sassoon and the other war poets in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (log in with your library card).

September

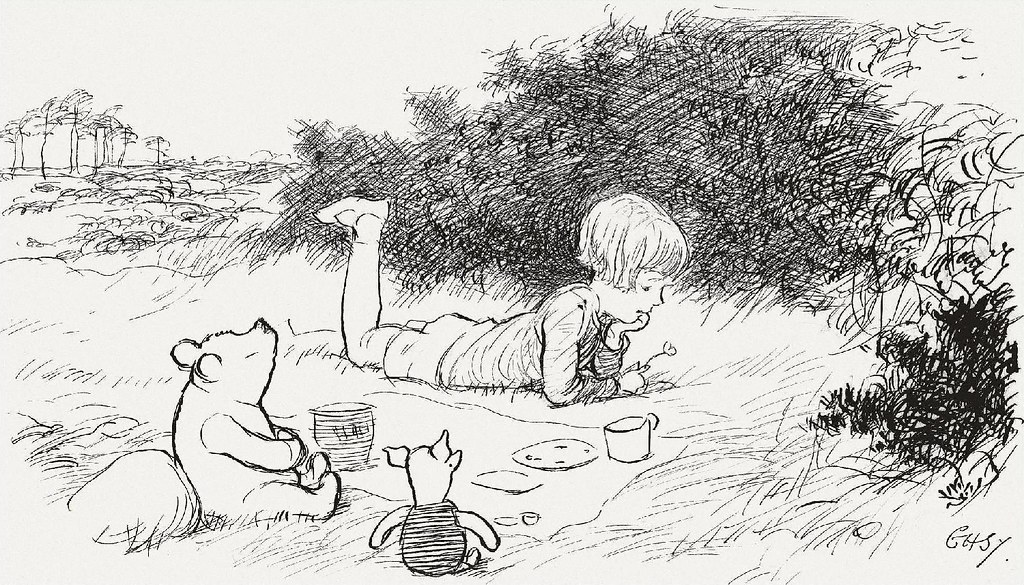

Another literary anniversary is upon us on 21 September, when we note the publication of one of the bestselling fantasy books of all time – The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien, about a small, shy creature who becomes involved in a quest for a dragon’s hoard. It was offered first to the publisher Stanley Unwin who asked his 10 year old son Raynor to review it for him,

“Bilbo Baggins was a Hobbit who lived in his Hobbit hole and never went for adventures, at last Gandalf the wizard and his Dwarves persuaded him to go. He had a very exiting (sic) time fighting goblins and wargs. At last they get to the lonely mountain; Smaug, the dragon who guards it is killed and after a terrific battle with the goblins he returned home – rich!

This book, with the help of maps, does not need any illustrations it is good and should appeal to all children between the ages of 5 and 9.”

The book was an instant success thanks to glowing newspaper reviews (The Manchester Guardian wrote ‘The quest of the dragon’s treasure – rightfully the dwarves treasure – makes an exciting epic of travel, magical adventures, and – working up to a devastating climax, war. Not a story for pacifist children. Or is it?’) and has never been out of print. While embarking on the sequel, The Lord of the Rings, is a pretty daunting task, The Hobbit is still funny and exciting and highly recommended to that clichéd group – children of all ages.

The book was an instant success thanks to glowing newspaper reviews (The Manchester Guardian wrote ‘The quest of the dragon’s treasure – rightfully the dwarves treasure – makes an exciting epic of travel, magical adventures, and – working up to a devastating climax, war. Not a story for pacifist children. Or is it?’) and has never been out of print. While embarking on the sequel, The Lord of the Rings, is a pretty daunting task, The Hobbit is still funny and exciting and highly recommended to that clichéd group – children of all ages.

October

The audience at Warner’s Theatre in New York on 6 October 1927 knew they were going to see an exciting new movie, but none of them could have predicted that motion pictures would never be the same again. The Jazz Singer was the first feature film with synchronised singing – no dialogue had been planned but the star, Al Jolson, couldn’t resist adlibbing on set and his ‘Wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothing yet’ (in fact, his stage catchphrase) has electrified audiences ever since.

The film was a huge hit making over $2,000,000 (having cost only $400,000) and Jolson became an international star. The movies didn’t look back and within three years, silent film was a thing of the past.

To be honest, seen now, the film (about a Jewish boy who defies his father to sing jazz) is slow, sentimental and creaky, and the less said about Al Jolson’s penchant for blackface the better, but it’s worth checking out his performance to see the sort of charisma that sold out Broadway theatres for 20 years.

To be honest, seen now, the film (about a Jewish boy who defies his father to sing jazz) is slow, sentimental and creaky, and the less said about Al Jolson’s penchant for blackface the better, but it’s worth checking out his performance to see the sort of charisma that sold out Broadway theatres for 20 years.

You can also see how fan magazines reported it at the time by checking out the Lantern site – a fantastic archive of Hollywood magazines that will keep film buffs busy for days…

November

As of 2015 there were 5640 female clergy in the Church of England (with 14,820 men) and it’s predicted that women will make up 43% of the clergy by 2035. Yet the General Synod only voted to allow women priests (against fierce opposition from conservatives) on 25 November 1992. Now they are central to the life of the Church of England and most of their opponents have been won over. Some of this can, of course, be attributed to The Vicar of Dibley with Dawn French as the eponymous lady priest, but they’re now so much part of the landscape that even Ambridge, home of the Archers has had a woman vicar.

December

3 December will be the 50th anniversary of the first heart transplant operation, performed by the South African surgeon Christian Barnard. The first patient, Lewis Washkansky, died 18 days after the operation (though he was able to walk and talk after the transplant). The second patient to receive a heart was a baby who sadly didn’t survive the operation, but the third patient, Philip Blaiberg lived for another nineteen months. Six months later, in May 1968, the first British heart transplant took place at the National Heart Hospital in Westmoreland Street, Marylebone. Now about 3,500 heart transplants take place each year and 50% of patients live for at least 10 years. So while none of us want one, it’s good to know they’re available.

You can find out more about these events and many more in our 24/7 library and of course the in the libraries themselves. Happy 2017!

[Nicky]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Westminster Libraries’ users, unless they’ve been living under a rock, will know that today is the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. Quite a lot of us probably think of it as his birthday too though that is a

Westminster Libraries’ users, unless they’ve been living under a rock, will know that today is the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. Quite a lot of us probably think of it as his birthday too though that is a  Top of the list is Spain’s most famous author

Top of the list is Spain’s most famous author

One of the great unsung heroes of medicine will be remembered on 1 January (or if he isn’t, he should be!). On that date in 1916,

One of the great unsung heroes of medicine will be remembered on 1 January (or if he isn’t, he should be!). On that date in 1916,