All of us who live or work in Westminster have walked through Trafalgar Square dozens of times, but how many of us have actually looked at Nelson’s Column properly? Certainly not me until recently when I happened to look at the bas-reliefs at the base of the pillar and wondered what they actually represented. Coincidentally on the bus home I heard a trailer for an excellent-sounding radio programme, Britain’s Black Past which mentioned the reliefs and revealed that at least one of the sailors pictured was black. A bit of research revealed that a third of the crew of the Victory, Nelson’s ship, were born outside Britain (including, somewhat surprisingly, three Frenchmen) and that one of the men pictured, George Ryan, was black.

As we celebrate Black History Month, what other memorials of interest can we find in Westminster?

Well, for a start there’s the oldest monument in London – Cleopatra’s Needle. Nothing to do with Cleopatra, it actually predates her by 1500 years, being made for Pharoah Thotmes III. One slightly odd feature of the Needle is that the four sphinxes, ostensibly there to guard it, actually face inwards so you’d think they’d be fairly easy to surprise…

Moving forward to the eighteenth century brings us to Ignatius Sancho (1724-1780) who, despite pretty much the worst possible start in life (he was born on slave ship and both his parents died soon after) became butler to the Duke of Montagu and, after securing his freedom, was the only eighteenth-century Afro-Briton known to have voted in a general election (in Westminster). He wrote many letters to the literary figures of the time such as the actor David Garrick and the writer Laurence Sterne, was painted by Thomas Gainsborough and was also a prolific composer.

You can read more about Sancho in several books available to view at Westminster City Archives, and listen to some of his compositions.

And if you happen to be passing the Foreign and Commonweath Office, see if you can spot the memorial to him.

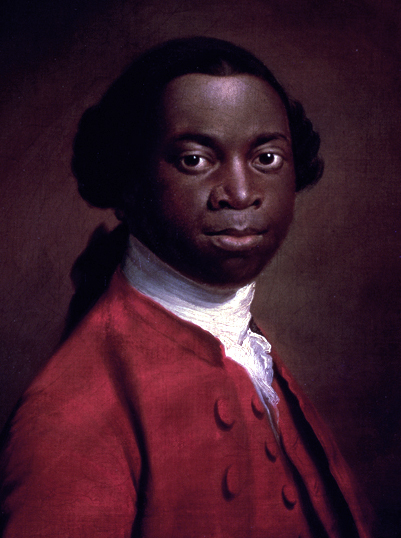

A more famous near-contemporary of Sancho, was Olaudah Equiano (1747-1797), another former slave and author of one of the earliest autobiographies by a black Briton.

Like George Ryan, Equiano (or Gustavus Vassa as he was known in his lifetime) was a sailor who travelled to the Caribbean, South America and the Arctic, having been kidnapped from Africa as a child. While still a slave, Equiano converted to Christianity and was baptised in St Margaret’s Westminster. His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano was one of the first slave narratives and was reprinted several times in Equiano’s lifetime. He became a leading member of the abolitionist movement, as one of the Sons of Africa, a group of former slaves in London who campaigned against slavery. You can see a plaque to him at 73 Riding House Street, Paddington and see him portrayed by Youssoo N’Dour in the film Amazing Grace.

One black Briton who needs almost no introduction is Mary Seacole (1805-1881), who fought racial prejudice to nurse and feed soldiers in the Crimea and who was so popular with her former patients that the Times reported on 26th April 1856 that, at a public banquet at the Royal Surrey Gardens:

“Among the illustrious visitors was Mrs Seacole whose appearance awakened the most raputurous enthusiasm. The soldiers not only cheered her but chaired her around the gardens and she really might have suffocated from the oppressive attentions of her admirers were it not that two sergeants of extraordinary stature gallantly undertook to protect her from the pressures of the crowd.”

You can follow the famous war correspondent WH Russell in the Times Digital Archive (log in with your library card number) – he was a great admirer of Mrs Seacole. And if you haven’t already, do read her extraordinary autobiography The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands. There are two plaques in her honour in Westminster – one at 147 George Street and one at 14 Soho Square.

Less well-known than Mary Seacole is Henry Sylvester Williams (1869-1911), a Trinidadian teacher who came to London in the 1890s, studied Latin at King’s College and qualified as a barrister in 1897 (though he earned his living as a lecturer for the Temperance Association). He was a founder-member of the Pan-African Association, whose aims were

“to secure civil and political rights for Africans and their descendants throughout the world; to encourage African peoples everywhere in educational, industrial and commercial enterprise; to ameliorate the condition of the oppressed Negro in Africa, America, the British Empire, and other parts of the world”

In 1906, Williams was elected as a Progressive for Marylebone Council and, along with John Archer in Battersea, was one of the first black people elected to public office in Britain. You can read more about Williams (and the other people listed here) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and see a plaque erected by Westminster Council in his honour at 38 Church Street.

Bringing us nearer the present day are two former residents of Westminster who everyone knows. Guitarist Jimi Hendrix, discussed before in this blog, lived for a short time in 1968 at 23 Brook Street, Mayfair, and you can see a blue plaque to him there.

And we finish on perhaps the most famous memorial of recent years – in 2007 a bronze statue of Nelson Mandela was erected in Parliament Square in the presence of Mr Mandela himself.

You can find out more about the people in this blog by checking out our library catalogue and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as well as our Newspaper Archives. Plus if you want to know who the first Black British woman to write an autobiography was, don’t miss the event at Paddington Library on 27 October!

[Nicky]

.jpg)

In the last week of September Marylebone gained another blue plaque with the unveiling in Wyndham Place W1 of a plaque to

In the last week of September Marylebone gained another blue plaque with the unveiling in Wyndham Place W1 of a plaque to  Many other towns have set up their own commemorative plaque scheme, but not all plaques are official. For several years in Reading’s Zinzan Street this unofficial example brought a smile to the face of many a passer by…

Many other towns have set up their own commemorative plaque scheme, but not all plaques are official. For several years in Reading’s Zinzan Street this unofficial example brought a smile to the face of many a passer by…