How the Bridgerton like excess of Regency London radicalised Life Guard John Harrison

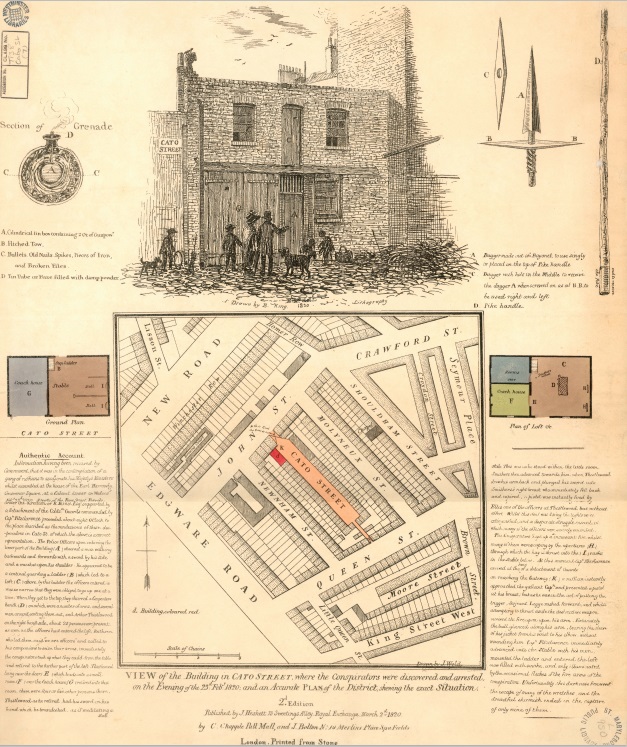

Thanks to a grant from the Heritage Fund, Westminster Archives has been working to commemorate the bicentenary of The Cato Street Conspiracy. This was an attempt on February 23rd ,1820, to assassinate Prime Minister Lord Liverpool and his cabinet in Grosvenor Square and spark a British version of the French Revolution.

George III died on 29th January 1820. This was just three weeks before the Cato Street Conspiracy took place in the dying embers of the period we now know as the Regency. This was a period of momentous events, and stark contrasts; a society forced to confront a whole range of pressing new issues that signalled a decisive break from the past and an era, which brought our modern world clearly into view. This is the period Netflix have sought to bring alive through their recent smash hit series Bridgerton. However, as with many big screen depictions, they channel the world of Jane Austen and the Romantic poets; the countryside of John Constable and the sartorial elegance of Beau Brummell. It’s an extravagant world of opulence that the producers of Bridgerton admit was their aim. Bridgerton’s Regency London is thus a fantasy world. Viewers are kept away from the stark realities of a time where immense poverty stoked the fires of revolution. This real Regency London was the backdrop for the Cato Street Conspiracy.

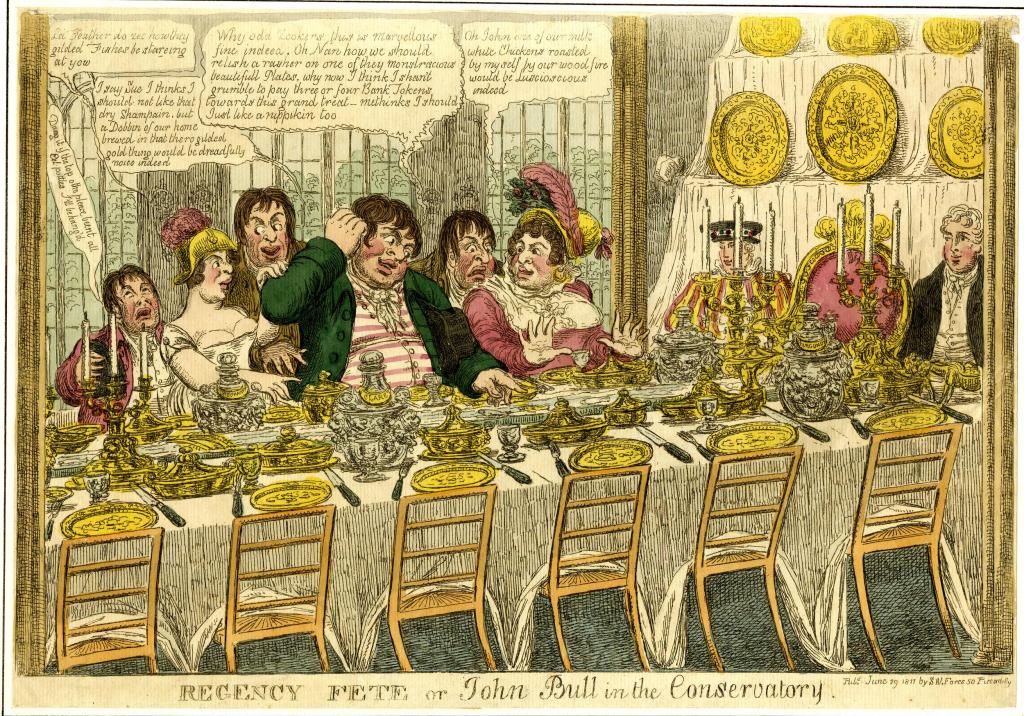

The Regency era had begun on 5th February 1811 when the Prince of Wales replaced his violently insane father George III as the sovereign in all but name. One of the Cato Street conspirators was present at the grand society ball that saw its birth. This was former Life Guard John Harrison, the man who was later responsible for sourcing and renting the conspirators hideout in Cato Street. Harrison’s proximity to the selfish and corpulent figure of the Prince Regent was a key factor in turning him into a revolutionary. As a trooper in the 2nd Life Guards, he was present on 19 June 1811, for the Prince Regent’s Fete. This was a magnificent dinner and ball held at Carlton House to celebrate the onset of the Regency. More than two thousand invitations were sent out for the most prestigious event of the year. These guests were part of “The Ton” -members of Regency high society-a term familiar to those who have been watching ‘Bridgerton.’ This came from the French “le bon ton” indicating a desire to be considered ‘fashionable people.’ Fashion was an obsession of the Prince Regent. As Colonel of the Life Guards, he ordered John Harrison and his fellow Life Guards to stand on parade at the dinner dressed in the new uniforms he had designed for the occasion. He was said to be delighted with their turnout, but not delighted enough to foot the cost of their new finery. This was something the poor troopers themselves were expected to cover from their own pockets. The Life Guards were effectively part of the Carlton House decorations, their tasteful new uniforms designed to blend with the Prince’s carefully selected crimson silk drapes, which formed the ornate canopy, which covered the enthroned Prince. John would have witnessed the un-soldierly Regent dressed in the uniform of a Field Marshall greeting the remnants of the original bon ton- those members of the French royal family who had escaped the revolutionary guillotine. Eight years later he would be transformed from royal bodyguard to revolutionary. What pushed him into taking this course?

John Harrison’s participation in the Regency Fete allowed our project an opportunity to try and answer this question. It helped us to explain the anger many ordinary people like John felt with how they were being governed at the start of the nineteenth century. Westminster Archives volunteers Amber Hederer and Becca Simons used this story in a small exhibition for our partner, The Household Cavalry Museum. We also used an actor interpreter in role as John Harrison to recount his story for local schools who visited the Cato Street site.

As part of this work we commissioned Freelance artist Kate Morton to recreate the scene from the Regency Fete based on a period prints and contemporary accounts. We wanted Kate to create a picture that would help us explain how a royal bodyguard became a revolutionary.

We were also able to inform Kate’s work through a contemporary description of the fete by one of John Harrison’s fellow Life Guards Sgt Major Thomas Playford. He described in his diary how the Life Guards were allowed to dig into the leftover food at the end of the evening:

“I was on duty at Carlton House, in June 1811, when the Prince of Wales gave a splendid fete on his assuming the full powers of Regency; his father, George the Third, being afflicted with insanity. At this fete my station was at the corner of one of the principal tables in the banqueting room. Among other things wonderful to a youth from the worlds of Yorkshire, was a stream of water along the centre of the tables, with fish of the golden and silver kinds swimming in the water. After the princes and nobility had retired to the ballroom, the guards were invited to partake of the banquet. We sat in the Prince Regent’s chair and drank his wine. ” [Memoir of Sergeant Major Thomas Playford, 2nd Life Guards 19th June 1811]

At a time of widespread starvation, Harrison would have been disgusted with the extravagance of the fare that was set to go to waste. Silver tureens of soup, dishes piled high with all kinds of roast meat, bowls of peaches, grapes, pineapples, and every other minor fruit in and out of season were left uneaten on the tables. Whilst the Regent’s guests gorged themselves on such bountiful fare and guzzled iced champagne smuggled from Napoleon’s France, many people in Britain were starving.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was not alone in commenting on such extravagance at a time of widespread starvation caused by the Napoleonic Wars:

“What think you of the bubbling brooks and mossy banks at Carlton House?” asked Shelley. “It is said that this entertainment will cost £120,000. Nor will it be the last bauble which the nation must buy to amuse this overgrown bantling of Regency.”

The Napoleonic blockade of Britain had served most of those gathered in Carlton House well. The “Ton” -the landowning elite- were able to benefit from the high prices they could charge for the wheat grown on their farms. They would late use their political power to pass the hated Corn Laws to ensure those high prices continued.

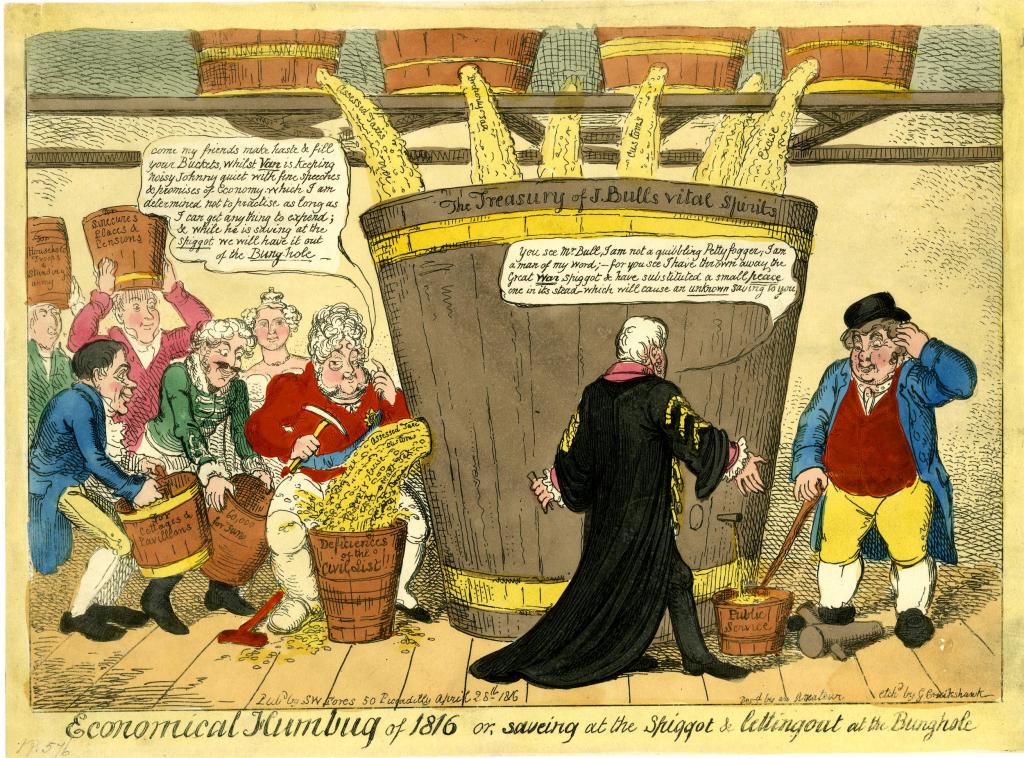

George Cruikshank 1816 British Museum 1859,0316.116

By the time Cruikshank published his 1816 cartoon condemning the behaviour of the Prince Regent and his friends from the “Ton,” Harrison had left the Life Guards and found work in London as a baker. He saw first-hand the impact the price of bread had on the poor.

Harrison had fought under Wellington in the Peninsular Campaign and on his return to England in 1814 faced unemployment and hunger as a reward for his service. The disillusioned Harrison sought comradery and found it at The Marylebone Union Reading Society. This was based at school teacher Thomas Hazard’s house at 54 Queen Street (now Harrowby Street) close to Edgware Road. The society’s members paid a subscription of two pence a week and collectively purchased radical pamphlets and newspapers to read aloud and debate. The members of the society helped Harrison, and one even found him employment as a baker.

Among the company of the Reading Society, Harrison soon fell in with a group of radicals known as the Spencean Philanthropists. They despised the landed classes and sought a revolution that would abolish private property and divide land equally amongst the people. After the Peterloo massacre in 1819, the Spenceans began plotting what would later be known as the Cato Street Conspiracy.

John Harrison was tasked with finding the group a suitable base from which they could launch their attack on Lord Liverpool’s government. Harrison came up with a stable at Cato Street, which was close to his former Life Guard barracks at King Street. The stable had been erected around 1803 as a gentleman’s stable and coach-house, and it stood in an unpaved lane of cottages for labourers.

In late 1819 the stable belonged to an Indian army officer, General Watson, whose agent let it to Harrison. The barn was perfect because it was in a secluded mews alley close to their intended target. This was Lord Harrowby’s house at 39, Grosvenor Square. Harrison had claimed he wanted to keep his horse and cart there. In truth, he was really looking for somewhere for himself and his friends to meet before they ventured forth in hope of changing the course of history.

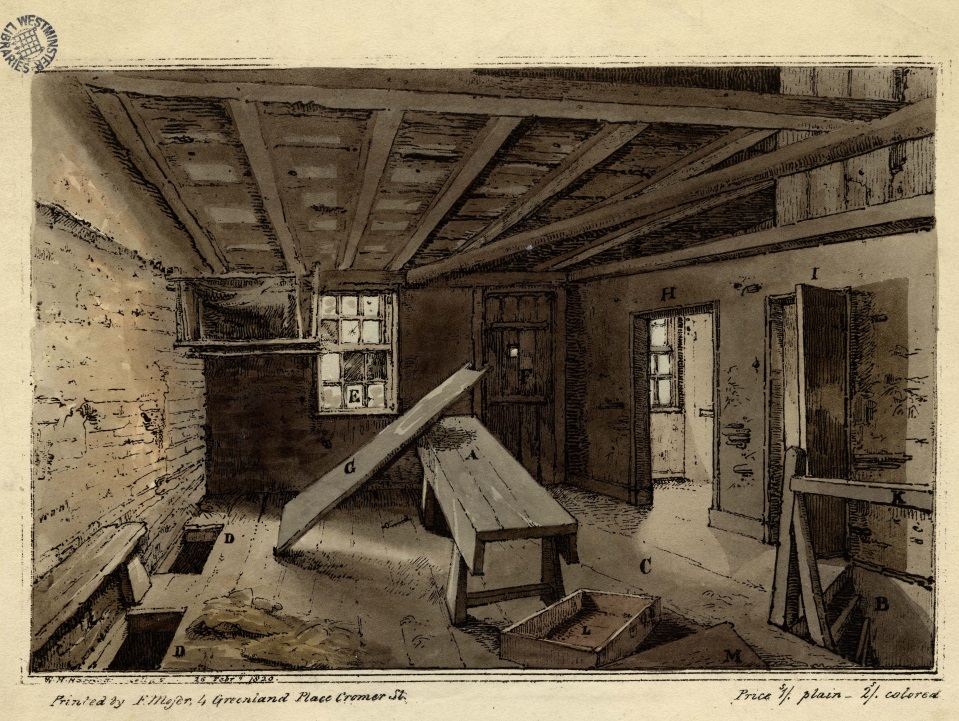

As part of our Heritage project we worked with Rob Nutter and his team of volunteers from RH Viz. Using images from Westminster Archives Ashbridge collection and estate agents plans from Right Move (the site in Cato Street was put up for sale in February 2020). Rob was able to recreate the interior of the Cato Street Conspirators’ hideout as it would have looked on the night of February 23rd ,1820. The Cato Street premises is now a comfortable mews flat that was on sale for £1.4m in February 2020. As part of our Heritage project we wanted people to be able to step through its doors and experience its interior as John Harrison would have seen it in 1820. RH Viz has created both a short video and a 3D VR experience which we hope to engage the public with once the Covid 19 epidemic allows.

For more information, visit our website: www.catostreetconspiracy.org.uk

RH Viz Cato Street barn MP4

The Cato Street Conspiracy project was funded thanks to the generosity of players of the National Lottery by a £74,000 grant from the Heritage Fund.